How Hearing Works

At Hearingworks, Kew, we help our clients to understand how hearing works and how hearing can deteriorate.

Our hearing is very complex. A very simple explanation is that your outer ear directs sound waves to your eardrum and causes it to vibrate. These vibrations move through your middle ear via three tiny bones and into the cochlear in your inner ear. The cochlea converts the vibrations into electrical signals that travel to your brain, which in turn translates them into what you hear.

(Fun facts: The name cochlea comes from the ancient Greek word for spiral, snail shell. The cochlea is about the size of a pea.)

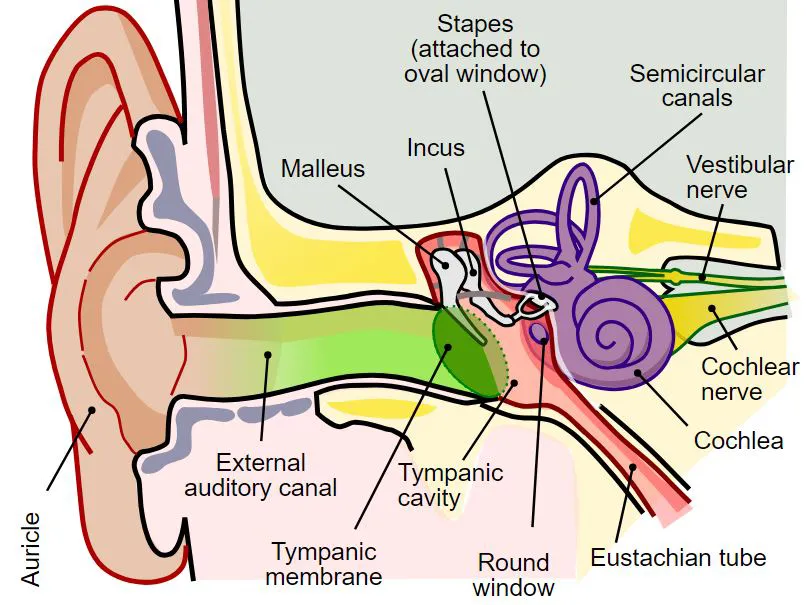

For a more detailed explanation of how hearing works look at this diagram and read the description below.

Parts of the ear and auditory system:

The outer ear is made up of the skin and cartilage (pinna or auricle) on each side of your head, and the ‘ear canal’ that leads into your head. The opening (concha) in the auricle funnels sound waves into the ear canal and it also helps to identify the direction from which the sound is coming. The ear canal can vary in size and shape and it runs horizontally for about 2.5 cm inside your head. The skin along the outer part of the ear canal has stiff hairs that produce ear wax (cerumen). This ear wax performs an important function, as it prevents foreign objects and bugs from entering the ear and it helps to stop the skin of the ear canal from drying out.

The middle ear starts at the cone shaped ear drum (tympanic membrane) located at the end of your ear canal. Behind the ear drum is an air-filled ‘tympanic cavity’ that contains three little connected bones known as the ‘ossicles’ and they have nicknames of ‘hammer’ (malleus), ‘anvil’ (incus) and ‘stirrup’ (stapes). The hammer is connected to the ear drum at one end of the chain and the stirrup (the smallest bone in the human body) rests against another membrane called the ‘oval window’ (fenestra ovalis). Just below the oval window is yet another membrane called the ‘round window’. The stirrup rapidly moves like a piston against the oval window causing it to vibrate in and out, which in turn pushes the fluid in the cochlea (see below). The round window is flexible, so it allows the fluid to be displaced.

The middle ear cavity is also connected to the back of the nose and throat by the ‘Eustachian tube’. The purpose of this tube is to equalise the air pressure in the middle ear space to be the same as that on the outside of the ear drum. It is normally closed but opens when we swallow or yawn or blow our nose. It is often uncomfortable when flying, or even when going up a mountain, and your ears may go ‘pop’. It helps to force a yawn or swallow to ease the pressure on your ear drum.

The inner ear contains the shell-shaped ‘cochlea’, which is filled with liquid that carries the vibrations from the oval window to thousands of very small hair cells (stereocilia) along the length of the cochlea. Each cell is tuned to a particular frequency. As these hair cells move in the fluid, they carry an electrical message to the ‘auditory nerve’ that is connected to your brain, which interprets it into what you perceive as sound. The inner ear also includes the ‘semi-circular canals’ that controls your balance.

This process is incredibly fast and complex, allowing us to not only hear a wide range of sounds, from the rustling of leaves to the melody of a song, but also locate the source of a sound and understand speech. Our ability to hear is vital for communication, safety, and our overall experience of the world around us.

However, it is also very delicate and can be damaged by exposure to loud noises, ear infections, drugs, head injury, tumour or by hereditary factors. If you experience hearing loss or other issues with your hearing or balance, it’s important to consult a doctor or audiologist.

Book an appointment online or call 03 9817 7738 or visit our clinic at 91 Cotham Rd, Cotham Village, Kew, at the T-intersection of Glenferrie Rd and Cotham Rd, to book an appointment